Differential calculus is an important tool in machine learning algorithms. Neural networks in particular, the gradient descent algorithm depends on the gradient, which is a quantity computed by differentiation.

In this tutorial, we will see how the back-propagation technique is used in finding the gradients in neural networks.

After completing this tutorial, you will know

- What is a total differential and total derivative

- How to compute the total derivatives in neural networks

- How back-propagation helped in computing the total derivatives

Let’s get started

Application of differentiations in neural networks

Photo by Freeman Zhou, some rights reserved.

Tutorial overview

This tutorial is divided into 5 parts; they are:

- Total differential and total derivatives

- Algebraic representation of a multilayer perceptron model

- Finding the gradient by back-propagation

- Matrix form of gradient equations

- Implementing back-propagation

Total differential and total derivatives

For a function such as $f(x)$, we call denote its derivative as $f'(x)$ or $\frac{df}{dx}$. But for a multivariate function, such as $f(u,v)$, we have a partial derivative of $f$ with respect to $u$ denoted as $\frac{\partial f}{\partial u}$, or sometimes written as $f_u$. A partial derivative is obtained by differentiation of $f$ with respect to $u$ while assuming the other variable $v$ is a constant. Therefore, we use $\partial$ instead of $d$ as the symbol for differentiation to signify the difference.

However, what if the $u$ and $v$ in $f(u,v)$ are both function of $x$? In other words, we can write $u(x)$ and $v(x)$ and $f(u(x), v(x))$. So $x$ determines the value of $u$ and $v$ and in turn, determines $f(u,v)$. In this case, it is perfectly fine to ask what is $\frac{df}{dx}$, as $f$ is eventually determined by $x$.

This is the concept of total derivatives. In fact, for a multivariate function $f(t,u,v)=f(t(x),u(x),v(x))$, we always have

$$

\frac{df}{dx} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t}\frac{dt}{dx} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial u}\frac{du}{dx} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial v}\frac{dv}{dx}

$$

The above notation is called the total derivative because it is sum of the partial derivatives. In essence, it is applying chain rule to find the differentiation.

If we take away the $dx$ part in the above equation, what we get is an approximate change in $f$ with respect to $x$, i.e.,

$$

df = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t}dt + \frac{\partial f}{\partial u}du + \frac{\partial f}{\partial v}dv

$$

We call this notation the total differential.

Algebraic representation of a multilayer perceptron model

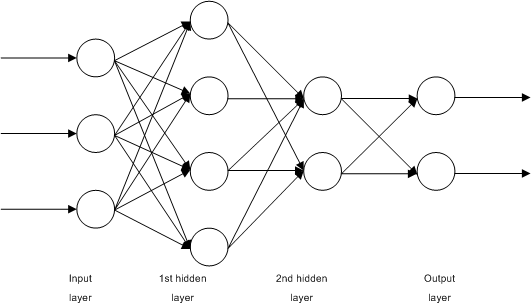

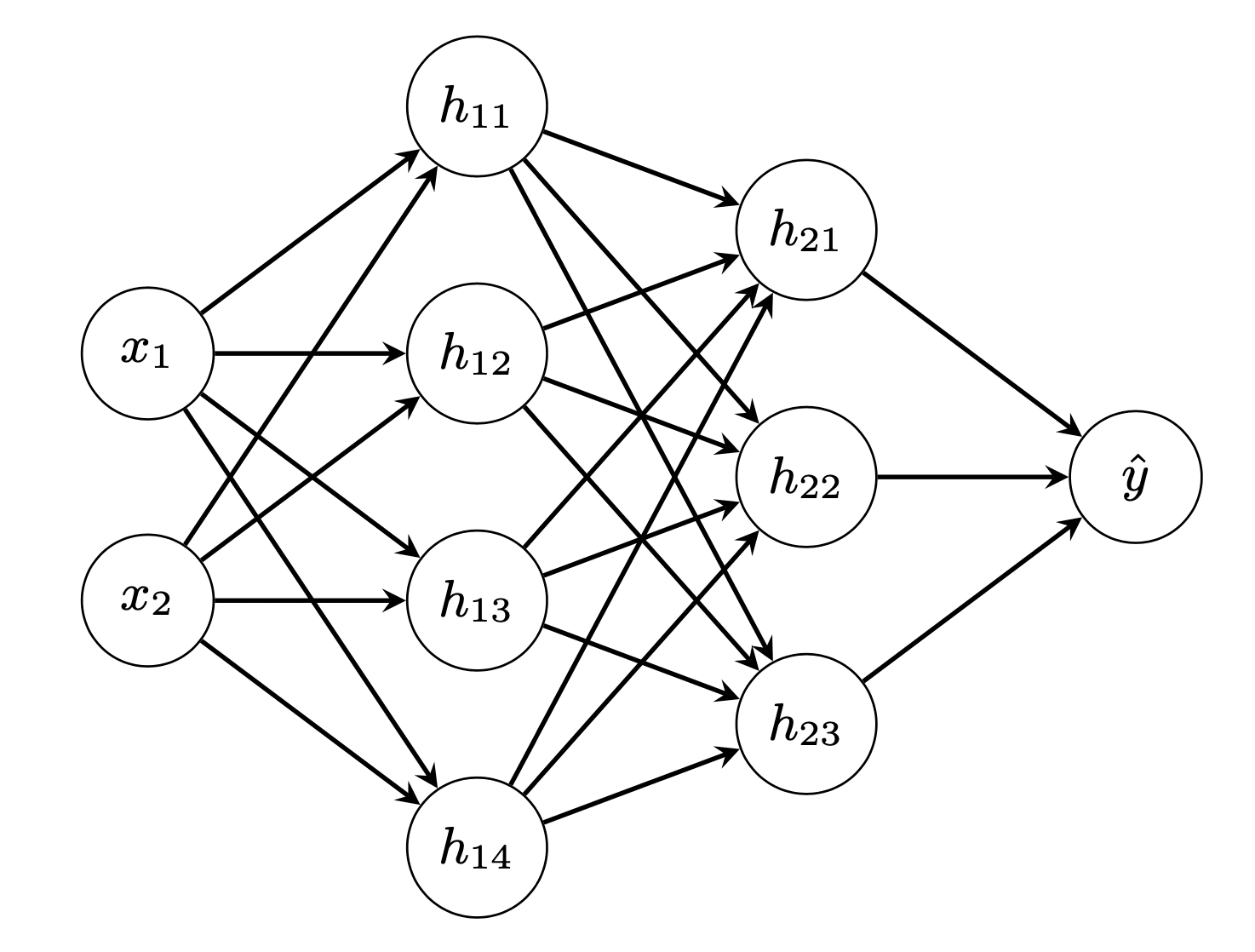

Consider the network:

An example of neural network. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Multilayer_Neural_Network.png

This is a simple, fully-connected, 4-layer neural network. Let’s call the input layer as layer 0, the two hidden layers the layer 1 and 2, and the output layer as layer 3. In this picture, we see that we have $n_0=3$ input units, and $n_1=4$ units in the first hidden layer and $n_2=2$ units in the second input layer. There are $n_3=2$ output units.

If we denote the input to the network as $x_i$ where $i=1,\cdots,n_0$ and the network’s output as $\hat{y}_i$ where $i=1,\cdots,n_3$. Then we can write

$$

\begin{aligned}

h_{1i} &= f_1(\sum_{j=1}^{n_0} w^{(1)}_{ij} x_j + b^{(1)}_i) & \text{for } i &= 1,\cdots,n_1\\

h_{2i} &= f_2(\sum_{j=1}^{n_1} w^{(2)}_{ij} h_{1j} + b^{(2)}_i) & i &= 1,\cdots,n_2\\

\hat{y}_i &= f_3(\sum_{j=1}^{n_2} w^{(3)}_{ij} h_{2j} + b^{(3)}_i) & i &= 1,\cdots,n_3

\end{aligned}

$$

Here the activation function at layer $i$ is denoted as $f_i$. The outputs of first hidden layer are denoted as $h_{1i}$ for the $i$-th unit. Similarly, the outputs of second hidden layer are denoted as $h_{2i}$. The weights and bias of unit $i$ in layer $k$ are denoted as $w^{(k)}_{ij}$ and $b^{(k)}_i$ respectively.

In the above, we can see that the output of layer $k-1$ will feed into layer $k$. Therefore, while $\hat{y}_i$ is expressed as a function of $h_{2j}$, but $h_{2i}$ is also a function of $h_{1j}$ and in turn, a function of $x_j$.

The above describes the construction of a neural network in terms of algebraic equations. Training a neural network would need to specify a *loss function* as well so we can minimize it in the training loop. Depends on the application, we commonly use cross entropy for categorization problems or mean squared error for regression problems. With the target variables as $y_i$, the mean square error loss function is specified as

$$

L = \sum_{i=1}^{n_3} (y_i-\hat{y}_i)^2

$$

Want to Get Started With Calculus for Machine Learning?

Take my free 7-day email crash course now (with sample code).

Click to sign-up and also get a free PDF Ebook version of the course.

Finding the gradient by back-propagation

In the above construct, $x_i$ and $y_i$ are from the dataset. The parameters to the neural network are $w$ and $b$. While the activation functions $f_i$ are by design the outputs at each layer $h_{1i}$, $h_{2i}$, and $\hat{y}_i$ are dependent variables. In training the neural network, our goal is to update $w$ and $b$ in each iteration, namely, by the gradient descent update rule:

$$

\begin{aligned}

w^{(k)}_{ij} &= w^{(k)}_{ij} – \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial w^{(k)}_{ij}} \\

b^{(k)}_{i} &= b^{(k)}_{i} – \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial b^{(k)}_{i}}

\end{aligned}

$$

where $\eta$ is the learning rate parameter to gradient descent.

From the equation of $L$ we know that $L$ is not dependent on $w^{(k)}_{ij}$ or $b^{(k)}_i$ but on $\hat{y}_i$. However, $\hat{y}_i$ can be written as function of $w^{(k)}_{ij}$ or $b^{(k)}_i$ eventually. Let’s see one by one how the weights and bias at layer $k$ can be connected to $\hat{y}_i$ at the output layer.

We begin with the loss metric. If we consider the loss of a single data point, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

L &= \sum_{i=1}^{n_3} (y_i-\hat{y}_i)^2\\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i} &= 2(y_i – \hat{y}_i) & \text{for } i &= 1,\cdots,n_3

\end{aligned}

$$

Here we see that the loss function depends on all outputs $\hat{y}_i$ and therefore we can find a partial derivative $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}$.

Now let’s look at the output layer:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\hat{y}_i &= f_3(\sum_{j=1}^{n_2} w^{(3)}_{ij} h_{2j} + b^{(3)}_i) & \text{for }i &= 1,\cdots,n_3 \\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial w^{(3)}_{ij}} &= \frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}\frac{\partial \hat{y}_i}{\partial w^{(3)}_{ij}} & i &= 1,\cdots,n_3;\ j=1,\cdots,n_2 \\

&= \frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i} f’_3(\sum_{j=1}^{n_2} w^{(3)}_{ij} h_{2j} + b^{(3)}_i)h_{2j} \\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial b^{(3)}_i} &= \frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}\frac{\partial \hat{y}_i}{\partial b^{(3)}_i} & i &= 1,\cdots,n_3 \\

&= \frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}f’_3(\sum_{j=1}^{n_2} w^{(3)}_{ij} h_{2j} + b^{(3)}_i)

\end{aligned}

$$

Because the weight $w^{(3)}_{ij}$ at layer 3 applies to input $h_{2j}$ and affects output $\hat{y}_i$ only. Hence we can write the derivative $\frac{\partial L}{\partial w^{(3)}_{ij}}$ as the product of two derivatives $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}\frac{\partial \hat{y}_i}{\partial w^{(3)}_{ij}}$. Similar case for the bias $b^{(3)}_i$ as well. In the above, we make use of $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}$, which we already derived previously.

But in fact, we can also write the partial derivative of $L$ with respect to output of second layer $h_{2j}$. It is not used for the update of weights and bias on layer 3 but we will see its importance later:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2j}} &= \sum_{i=1}^{n_3}\frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}\frac{\partial \hat{y}_i}{\partial h_{2j}} & \text{for }j &= 1,\cdots,n_2 \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^{n_3}\frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}f’_3(\sum_{j=1}^{n_2} w^{(3)}_{ij} h_{2j} + b^{(3)}_i)w^{(3)}_{ij}

\end{aligned}

$$

This one is the interesting one and different from the previous partial derivatives. Note that $h_{2j}$ is an output of layer 2. Each and every output in layer 2 will affect the output $\hat{y}_i$ in layer 3. Therefore, to find $\frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2j}}$ we need to add up every output at layer 3. Thus the summation sign in the equation above. And we can consider $\frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2j}}$ as the total derivative, in which we applied the chain rule $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{y}_i}\frac{\partial \hat{y}_i}{\partial h_{2j}}$ for every output $i$ and then sum them up.

If we move back to layer 2, we can derive the derivatives similarly:

$$

\begin{aligned}

h_{2i} &= f_2(\sum_{j=1}^{n_1} w^{(2)}_{ij} h_{1j} + b^{(2)}_i) & \text{for }i &= 1,\cdots,n_2\\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial w^{(2)}_{ij}} &= \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2i}}\frac{\partial h_{2i}}{\partial w^{(2)}_{ij}} & i&=1,\cdots,n_2;\ j=1,\cdots,n_1 \\

&= \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2i}}f’_2(\sum_{j=1}^{n_1} w^{(2)}_{ij} h_{1j} + b^{(2)}_i)h_{1j} \\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial b^{(2)}_i} &= \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2i}}\frac{\partial h_{2i}}{\partial b^{(2)}_i} & i &= 1,\cdots,n_2 \\

&= \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2i}}f’_2(\sum_{j=1}^{n_1} w^{(2)}_{ij} h_{1j} + b^{(2)}_i) \\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{1j}} &= \sum_{i=1}^{n_2}\frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2i}}\frac{\partial h_{2i}}{\partial h_{1j}} & j&= 1,\cdots,n_1 \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^{n_2}\frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2i}}f’_2(\sum_{j=1}^{n_1} w^{(2)}_{ij} h_{1j} + b^{(2)}_i) w^{(2)}_{ij}

\end{aligned}

$$

In the equations above, we are reusing $\frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{2i}}$ that we derived earlier. Again, this derivative is computed as a sum of several products from the chain rule. Also similar to the previous, we derived $\frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{1j}}$ as well. It is not used to train $w^{(2)}_{ij}$ nor $b^{(2)}_i$ but will be used for the layer prior. So for layer 1, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

h_{1i} &= f_1(\sum_{j=1}^{n_0} w^{(1)}_{ij} x_j + b^{(1)}_i) & \text{for } i &= 1,\cdots,n_1\\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial w^{(1)}_{ij}} &= \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{1i}}\frac{\partial h_{1i}}{\partial w^{(1)}_{ij}} & i&=1,\cdots,n_1;\ j=1,\cdots,n_0 \\

&= \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{1i}}f’_1(\sum_{j=1}^{n_0} w^{(1)}_{ij} x_j + b^{(1)}_i)x_j \\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial b^{(1)}_i} &= \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{1i}}\frac{\partial h_{1i}}{\partial b^{(1)}_i} & i&=1,\cdots,n_1 \\

&= \frac{\partial L}{\partial h_{1i}}f’_1(\sum_{j=1}^{n_0} w^{(1)}_{ij} x_j + b^{(1)}_i)

\end{aligned}

$$

and this completes all the derivatives needed for training of the neural network using gradient descent algorithm.

Recall how we derived the above: We first start from the loss function $L$ and find the derivatives one by one in the reverse order of the layers. We write down the derivatives on layer $k$ and reuse it for the derivatives on layer $k-1$. While computing the output $\hat{y}_i$ from input $x_i$ starts from layer 0 forward, computing gradients are in the reversed order. Hence the name “back-propagation”.

Matrix form of gradient equations

While we did not use it above, it is cleaner to write the equations in vectors and matrices. We can rewrite the layers and the outputs as:

$$

\mathbf{a}_k = f_k(\mathbf{z}_k) = f_k(\mathbf{W}_k\mathbf{a}_{k-1}+\mathbf{b}_k)

$$

where $\mathbf{a}_k$ is a vector of outputs of layer $k$, and assume $\mathbf{a}_0=\mathbf{x}$ is the input vector and $\mathbf{a}_3=\hat{\mathbf{y}}$ is the output vector. Also denote $\mathbf{z}_k = \mathbf{W}_k\mathbf{a}_{k-1}+\mathbf{b}_k$ for convenience of notation.

Under such notation, we can represent $\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{a}_k}$ as a vector (so as that of $\mathbf{z}_k$ and $\mathbf{b}_k$) and $\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{W}_k}$ as a matrix. And then if $\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{a}_k}$ is known, we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{z}_k} &= \frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{a}_k}\odot f_k'(\mathbf{z}_k) \\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{W}_k} &= \left(\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{z}_k}\right)^\top \cdot \mathbf{a}_k \\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{b}_k} &= \frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{z}_k} \\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{a}_{k-1}} &= \left(\frac{\partial\mathbf{z}_k}{\partial\mathbf{a}_{k-1}}\right)^\top\cdot\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{z}_k} = \mathbf{W}_k^\top\cdot\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{z}_k}

\end{aligned}

$$

where $\frac{\partial\mathbf{z}_k}{\partial\mathbf{a}_{k-1}}$ is a Jacobian matrix as both $\mathbf{z}_k$ and $\mathbf{a}_{k-1}$ are vectors, and this Jacobian matrix happens to be $\mathbf{W}_k$.

Implementing back-propagation

We need the matrix form of equations because it will make our code simpler and avoided a lot of loops. Let’s see how we can convert these equations into code and make a multilayer perceptron model for classification from scratch using numpy.

The first thing we need to implement the activation function and the loss function. Both need to be differentiable functions or otherwise our gradient descent procedure would not work. Nowadays, it is common to use ReLU activation in the hidden layers and sigmoid activation in the output layer. We define them as a function (which assumes the input as numpy array) as well as their differentiation:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

import numpy as np # Find a small float to avoid division by zero epsilon = np.finfo(float).eps # Sigmoid function and its differentiation def sigmoid(z): return 1/(1+np.exp(-z.clip(-500, 500))) def dsigmoid(z): s = sigmoid(z) return 2 * s * (1-s) # ReLU function and its differentiation def relu(z): return np.maximum(0, z) def drelu(z): return (z > 0).astype(float) |

We deliberately clip the input of the sigmoid function to between -500 to +500 to avoid overflow. Otherwise, these functions are trivial. Then for classification, we care about accuracy but the accuracy function is not differentiable. Therefore, we use the cross entropy function as loss for training:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

# Loss function L(y, yhat) and its differentiation def cross_entropy(y, yhat): """Binary cross entropy function L = - y log yhat - (1-y) log (1-yhat) Args: y, yhat (np.array): 1xn matrices which n are the number of data instances Returns: average cross entropy value of shape 1x1, averaging over the n instances """ return -(y.T @ np.log(yhat.clip(epsilon)) + (1-y.T) @ np.log((1-yhat).clip(epsilon))) / y.shape[1] def d_cross_entropy(y, yhat): """ dL/dyhat """ return - np.divide(y, yhat.clip(epsilon)) + np.divide(1-y, (1-yhat).clip(epsilon)) |

In the above, we assume the output and the target variables are row matrices in numpy. Hence we use the dot product operator @ to compute the sum and divide by the number of elements in the output. Note that this design is to compute the average cross entropy over a batch of samples.

Then we can implement our multilayer perceptron model. To make it easier to read, we want to create the model by providing the number of neurons at each layer as well as the activation function at the layers. But at the same time, we would also need the differentiation of the activation functions as well as the differentiation of the loss function for the training. The loss function itself, however, is not required but useful for us to track the progress. We create a class to ensapsulate the entire model, and define each layer $k$ according to the formula:

$$

\mathbf{a}_k = f_k(\mathbf{z}_k) = f_k(\mathbf{a}_{k-1}\mathbf{W}_k+\mathbf{b}_k)

$

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 |

class mlp: '''Multilayer perceptron using numpy ''' def __init__(self, layersizes, activations, derivatives, lossderiv): """remember config, then initialize array to hold NN parameters without init""" # hold NN config self.layersizes = layersizes self.activations = activations self.derivatives = derivatives self.lossderiv = lossderiv # parameters, each is a 2D numpy array L = len(self.layersizes) self.z = [None] * L self.W = [None] * L self.b = [None] * L self.a = [None] * L self.dz = [None] * L self.dW = [None] * L self.db = [None] * L self.da = [None] * L def initialize(self, seed=42): np.random.seed(seed) sigma = 0.1 for l, (insize, outsize) in enumerate(zip(self.layersizes, self.layersizes[1:]), 1): self.W[l] = np.random.randn(insize, outsize) * sigma self.b[l] = np.random.randn(1, outsize) * sigma def forward(self, x): self.a[0] = x for l, func in enumerate(self.activations, 1): # z = W a + b, with `a` as output from previous layer # `W` is of size rxs and `a` the size sxn with n the number of data instances, `z` the size rxn # `b` is rx1 and broadcast to each column of `z` self.z[l] = (self.a[l-1] @ self.W[l]) + self.b[l] # a = g(z), with `a` as output of this layer, of size rxn self.a[l] = func(self.z[l]) return self.a[-1] |

The variables in this class z, W, b, and a are for the forward pass and the variables dz, dW, db, and da are their respective gradients that to be computed in the back-propagation. All these variables are presented as numpy arrays.

As we will see later, we are going to test our model using data generated by scikit-learn. Hence we will see our data in numpy array of shape “(number of samples, number of features)”. Therefore, each sample is presented as a row on a matrix, and in function forward(), the weight matrix is right-multiplied to each input a to the layer. While the activation function and dimension of each layer can be different, the process is the same. Thus we transform the neural network’s input x to its output by a loop in the forward() function. The network’s output is simply the output of the last layer.

To train the network, we need to run the back-propagation after each forward pass. The back-propagation is to compute the gradient of the weight and bias of each layer, starting from the output layer to the input layer. With the equations we derived above, the back-propagation function is implemented as:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

class mlp: ... def backward(self, y, yhat): # first `da`, at the output self.da[-1] = self.lossderiv(y, yhat) for l, func in reversed(list(enumerate(self.derivatives, 1))): # compute the differentials at this layer self.dz[l] = self.da[l] * func(self.z[l]) self.dW[l] = self.a[l-1].T @ self.dz[l] self.db[l] = np.mean(self.dz[l], axis=0, keepdims=True) self.da[l-1] = self.dz[l] @ self.W[l].T def update(self, eta): for l in range(1, len(self.W)): self.W[l] -= eta * self.dW[l] self.b[l] -= eta * self.db[l] |

The only difference here is that we compute db not for one training sample, but for the entire batch. Since the loss function is the cross entropy averaged across the batch, we compute db also by averaging across the samples.

Up to here, we completed our model. The update() function simply applies the gradients found by the back-propagation to the parameters W and b using the gradient descent update rule.

To test out our model, we make use of scikit-learn to generate a classification dataset:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

from sklearn.datasets import make_circles from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score # Make data: Two circles on x-y plane as a classification problem X, y = make_circles(n_samples=1000, factor=0.5, noise=0.1) y = y.reshape(-1,1) # our model expects a 2D array of (n_sample, n_dim) |

and then we build our model: Input is two-dimensional and output is one dimensional (logistic regression). We make two hidden layers of 4 and 3 neurons respectively:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

# Build a model model = mlp(layersizes=[2, 4, 3, 1], activations=[relu, relu, sigmoid], derivatives=[drelu, drelu, dsigmoid], lossderiv=d_cross_entropy) model.initialize() yhat = model.forward(X) loss = cross_entropy(y, yhat) print("Before training - loss value {} accuracy {}".format(loss, accuracy_score(y, (yhat > 0.5)))) |

We see that, under random weight, the accuracy is 50%:

|

1 |

Before training - loss value [[693.62972747]] accuracy 0.5 |

Now we train our network. To make things simple, we perform full-batch gradient descent with fixed learning rate:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

# train for each epoch n_epochs = 150 learning_rate = 0.005 for n in range(n_epochs): model.forward(X) yhat = model.a[-1] model.backward(y, yhat) model.update(learning_rate) loss = cross_entropy(y, yhat) print("Iteration {} - loss value {} accuracy {}".format(n, loss, accuracy_score(y, (yhat > 0.5)))) |

and the output is:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

Iteration 0 - loss value [[693.62972747]] accuracy 0.5 Iteration 1 - loss value [[693.62166655]] accuracy 0.5 Iteration 2 - loss value [[693.61534159]] accuracy 0.5 Iteration 3 - loss value [[693.60994018]] accuracy 0.5 ... Iteration 145 - loss value [[664.60120828]] accuracy 0.818 Iteration 146 - loss value [[697.97739669]] accuracy 0.58 Iteration 147 - loss value [[681.08653776]] accuracy 0.642 Iteration 148 - loss value [[665.06165774]] accuracy 0.71 Iteration 149 - loss value [[683.6170298]] accuracy 0.614 |

Although not perfect, we see the improvement by training. At least in the example above, we can see the accuracy was up to more than 80% at iteration 145, but then we saw the model diverged. That can be improved by reducing the learning rate, which we didn’t implement above. Nonetheless, this shows how we computed the gradients by back-propagations and chain rules.

The complete code is as follows:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 |

from sklearn.datasets import make_circles from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score import numpy as np np.random.seed(0) # Find a small float to avoid division by zero epsilon = np.finfo(float).eps # Sigmoid function and its differentiation def sigmoid(z): return 1/(1+np.exp(-z.clip(-500, 500))) def dsigmoid(z): s = sigmoid(z) return 2 * s * (1-s) # ReLU function and its differentiation def relu(z): return np.maximum(0, z) def drelu(z): return (z > 0).astype(float) # Loss function L(y, yhat) and its differentiation def cross_entropy(y, yhat): """Binary cross entropy function L = - y log yhat - (1-y) log (1-yhat) Args: y, yhat (np.array): nx1 matrices which n are the number of data instances Returns: average cross entropy value of shape 1x1, averaging over the n instances """ return -(y.T @ np.log(yhat.clip(epsilon)) + (1-y.T) @ np.log((1-yhat).clip(epsilon))) / y.shape[1] def d_cross_entropy(y, yhat): """ dL/dyhat """ return - np.divide(y, yhat.clip(epsilon)) + np.divide(1-y, (1-yhat).clip(epsilon)) class mlp: '''Multilayer perceptron using numpy ''' def __init__(self, layersizes, activations, derivatives, lossderiv): """remember config, then initialize array to hold NN parameters without init""" # hold NN config self.layersizes = tuple(layersizes) self.activations = tuple(activations) self.derivatives = tuple(derivatives) self.lossderiv = lossderiv assert len(self.layersizes)-1 == len(self.activations), \ "number of layers and the number of activation functions does not match" assert len(self.activations) == len(self.derivatives), \ "number of activation functions and number of derivatives does not match" assert all(isinstance(n, int) and n >= 1 for n in layersizes), \ "Only positive integral number of perceptons is allowed in each layer" # parameters, each is a 2D numpy array L = len(self.layersizes) self.z = [None] * L self.W = [None] * L self.b = [None] * L self.a = [None] * L self.dz = [None] * L self.dW = [None] * L self.db = [None] * L self.da = [None] * L def initialize(self, seed=42): """initialize the value of weight matrices and bias vectors with small random numbers.""" np.random.seed(seed) sigma = 0.1 for l, (insize, outsize) in enumerate(zip(self.layersizes, self.layersizes[1:]), 1): self.W[l] = np.random.randn(insize, outsize) * sigma self.b[l] = np.random.randn(1, outsize) * sigma def forward(self, x): """Feed forward using existing `W` and `b`, and overwrite the result variables `a` and `z` Args: x (numpy.ndarray): Input data to feed forward """ self.a[0] = x for l, func in enumerate(self.activations, 1): # z = W a + b, with `a` as output from previous layer # `W` is of size rxs and `a` the size sxn with n the number of data instances, `z` the size rxn # `b` is rx1 and broadcast to each column of `z` self.z[l] = (self.a[l-1] @ self.W[l]) + self.b[l] # a = g(z), with `a` as output of this layer, of size rxn self.a[l] = func(self.z[l]) return self.a[-1] def backward(self, y, yhat): """back propagation using NN output yhat and the reference output y, generates dW, dz, db, da """ assert y.shape[1] == self.layersizes[-1], "Output size doesn't match network output size" assert y.shape == yhat.shape, "Output size doesn't match reference" # first `da`, at the output self.da[-1] = self.lossderiv(y, yhat) for l, func in reversed(list(enumerate(self.derivatives, 1))): # compute the differentials at this layer self.dz[l] = self.da[l] * func(self.z[l]) self.dW[l] = self.a[l-1].T @ self.dz[l] self.db[l] = np.mean(self.dz[l], axis=0, keepdims=True) self.da[l-1] = self.dz[l] @ self.W[l].T assert self.z[l].shape == self.dz[l].shape assert self.W[l].shape == self.dW[l].shape assert self.b[l].shape == self.db[l].shape assert self.a[l].shape == self.da[l].shape def update(self, eta): """Updates W and b Args: eta (float): Learning rate """ for l in range(1, len(self.W)): self.W[l] -= eta * self.dW[l] self.b[l] -= eta * self.db[l] # Make data: Two circles on x-y plane as a classification problem X, y = make_circles(n_samples=1000, factor=0.5, noise=0.1) y = y.reshape(-1,1) # our model expects a 2D array of (n_sample, n_dim) print(X.shape) print(y.shape) # Build a model model = mlp(layersizes=[2, 4, 3, 1], activations=[relu, relu, sigmoid], derivatives=[drelu, drelu, dsigmoid], lossderiv=d_cross_entropy) model.initialize() yhat = model.forward(X) loss = cross_entropy(y, yhat) print("Before training - loss value {} accuracy {}".format(loss, accuracy_score(y, (yhat > 0.5)))) # train for each epoch n_epochs = 150 learning_rate = 0.005 for n in range(n_epochs): model.forward(X) yhat = model.a[-1] model.backward(y, yhat) model.update(learning_rate) loss = cross_entropy(y, yhat) print("Iteration {} - loss value {} accuracy {}".format(n, loss, accuracy_score(y, (yhat > 0.5)))) |

Further readings

The back-propagation algorithm is the center of all neural network training, regardless of what variation of gradient descent algorithms you used. Textbook such as this one covered it:

- Deep Learning, by Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville, 2016.

(https://www.amazon.com/dp/0262035618)

Previously also implemented the neural network from scratch without discussing the math, it explained the steps in greater detail:

Summary

In this tutorial, you learned how differentiation is applied to training a neural network.

Specifically, you learned:

- What is a total differential and how it is expressed as a sum of partial differentials

- How to express a neural network as equations and derive the gradients by differentiation

- How back-propagation helped us to express the gradients of each layer in the neural network

- How to convert the gradients into code to make a neural network model

Dear Dr Adrian,

If you look at any calculus textbook, we know how to differentiate a function.

For example

f(x) = sin(x)

f'(x) = cos(x)

f(x) = x^2

f'(x) = 2x.

When dealing with real data, we don’t have ‘textbook’ functions.

While I am aware differentiation occurs “behind the scenes”, when it comes to the code above, I am lost where in the code the differentiation is performed.

Question please: where in the code above is differentiation using matrices applied. I do see many matrix multiplication lines in the code, but want to know where differentiation is done.

Yes I am aware of multi-variable differentiation, again want to know the implementation of differentiation used in the code.

Thank you,

Anthony of Sydney

If you use sigmoid function as activation, you need to use the differentiation of sigmoid function in back propagation. See at the beginning of the last sample code, both have to be defined in order to work. The matrix is just the way to add up the full differential from partial differentials.

Hi Adrian,

Thanks for the post.

Just noticed one mistake:

def dsigmoid(z):

s = sigmoid(z)

return 2 * s * (1-s)

derivative of sigmoid(z) should be s*(1-s) instead of 2*s*(1-s)

Hi Ian…Thank you for the feedback! More details can be found here:

https://towardsdatascience.com/derivative-of-the-sigmoid-function-536880cf918e

Hi thank you for the great explanation.

One thing is that isn’t the gradient of loss w.r.t W_k in matrix form supposed to be (\partial L / \partial z_k)^T \cdot a_{k-1} instead of a_k?

Hi Won…Thank you for your feedback! You may find the following helpful:

https://towardsdatascience.com/a-quick-introduction-to-derivatives-for-machine-learning-people-3cd913c5cf33