Information theory is a subfield of mathematics concerned with transmitting data across a noisy channel.

A cornerstone of information theory is the idea of quantifying how much information there is in a message. More generally, this can be used to quantify the information in an event and a random variable, called entropy, and is calculated using probability.

Calculating information and entropy is a useful tool in machine learning and is used as the basis for techniques such as feature selection, building decision trees, and, more generally, fitting classification models. As such, a machine learning practitioner requires a strong understanding and intuition for information and entropy.

In this post, you will discover a gentle introduction to information entropy.

After reading this post, you will know:

- Information theory is concerned with data compression and transmission and builds upon probability and supports machine learning.

- Information provides a way to quantify the amount of surprise for an event measured in bits.

- Entropy provides a measure of the average amount of information needed to represent an event drawn from a probability distribution for a random variable.

Kick-start your project with my new book Probability for Machine Learning, including step-by-step tutorials and the Python source code files for all examples.

Let’s get started.

- Update Nov/2019: Added example of probability vs information and more on the intuition for entropy.

A Gentle Introduction to Information Entropy

Photo by Cristiano Medeiros Dalbem, some rights reserved.

Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- What Is Information Theory?

- Calculate the Information for an Event

- Calculate the Entropy for a Random Variable

What Is Information Theory?

Information theory is a field of study concerned with quantifying information for communication.

It is a subfield of mathematics and is concerned with topics like data compression and the limits of signal processing. The field was proposed and developed by Claude Shannon while working at the US telephone company Bell Labs.

Information theory is concerned with representing data in a compact fashion (a task known as data compression or source coding), as well as with transmitting and storing it in a way that is robust to errors (a task known as error correction or channel coding).

— Page 56, Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective, 2012.

A foundational concept from information is the quantification of the amount of information in things like events, random variables, and distributions.

Quantifying the amount of information requires the use of probabilities, hence the relationship of information theory to probability.

Measurements of information are widely used in artificial intelligence and machine learning, such as in the construction of decision trees and the optimization of classifier models.

As such, there is an important relationship between information theory and machine learning and a practitioner must be familiar with some of the basic concepts from the field.

Why unify information theory and machine learning? Because they are two sides of the same coin. […] Information theory and machine learning still belong together. Brains are the ultimate compression and communication systems. And the state-of-the-art algorithms for both data compression and error-correcting codes use the same tools as machine learning.

— Page v, Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms, 2003.

Want to Learn Probability for Machine Learning

Take my free 7-day email crash course now (with sample code).

Click to sign-up and also get a free PDF Ebook version of the course.

Calculate the Information for an Event

Quantifying information is the foundation of the field of information theory.

The intuition behind quantifying information is the idea of measuring how much surprise there is in an event. Those events that are rare (low probability) are more surprising and therefore have more information than those events that are common (high probability).

- Low Probability Event: High Information (surprising).

- High Probability Event: Low Information (unsurprising).

The basic intuition behind information theory is that learning that an unlikely event has occurred is more informative than learning that a likely event has occurred.

— Page 73, Deep Learning, 2016.

Rare events are more uncertain or more surprising and require more information to represent them than common events.

We can calculate the amount of information there is in an event using the probability of the event. This is called “Shannon information,” “self-information,” or simply the “information,” and can be calculated for a discrete event x as follows:

- information(x) = -log( p(x) )

Where log() is the base-2 logarithm and p(x) is the probability of the event x.

The choice of the base-2 logarithm means that the units of the information measure is in bits (binary digits). This can be directly interpreted in the information processing sense as the number of bits required to represent the event.

The calculation of information is often written as h(); for example:

- h(x) = -log( p(x) )

The negative sign ensures that the result is always positive or zero.

Information will be zero when the probability of an event is 1.0 or a certainty, e.g. there is no surprise.

Let’s make this concrete with some examples.

Consider a flip of a single fair coin. The probability of heads (and tails) is 0.5. We can calculate the information for flipping a head in Python using the log2() function.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

# calculate the information for a coin flip from math import log2 # probability of the event p = 0.5 # calculate information for event h = -log2(p) # print the result print('p(x)=%.3f, information: %.3f bits' % (p, h)) |

Running the example prints the probability of the event as 50% and the information content for the event as 1 bit.

|

1 |

p(x)=0.500, information: 1.000 bits |

If the same coin was flipped n times, then the information for this sequence of flips would be n bits.

If the coin was not fair and the probability of a head was instead 10% (0.1), then the event would be more rare and would require more than 3 bits of information.

|

1 |

p(x)=0.100, information: 3.322 bits |

We can also explore the information in a single roll of a fair six-sided dice, e.g. the information in rolling a 6.

We know the probability of rolling any number is 1/6, which is a smaller number than 1/2 for a coin flip, therefore we would expect more surprise or a larger amount of information.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

# calculate the information for a dice roll from math import log2 # probability of the event p = 1.0 / 6.0 # calculate information for event h = -log2(p) # print the result print('p(x)=%.3f, information: %.3f bits' % (p, h)) |

Running the example, we can see that our intuition is correct and that indeed, there is more than 2.5 bits of information in a single roll of a fair die.

|

1 |

p(x)=0.167, information: 2.585 bits |

Other logarithms can be used instead of the base-2. For example, it is also common to use the natural logarithm that uses base-e (Euler’s number) in calculating the information, in which case the units are referred to as “nats.”

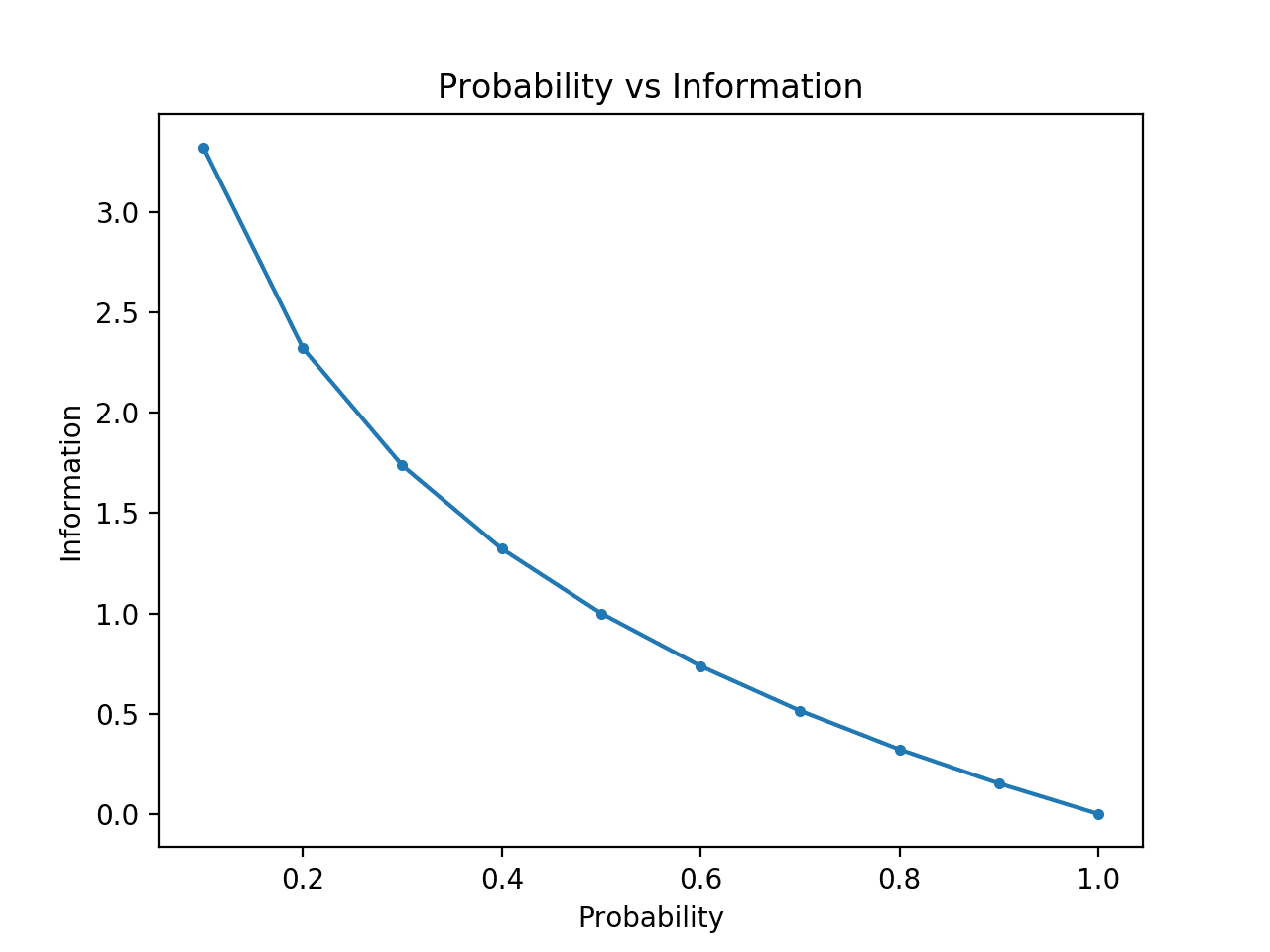

We can further develop the intuition that low probability events have more information.

To make this clear, we can calculate the information for probabilities between 0 and 1 and plot the corresponding information for each. We can then create a plot of probability vs information. We would expect the plot to curve downward from low probabilities with high information to high probabilities with low information.

The complete example is listed below.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

# compare probability vs information entropy from math import log2 from matplotlib import pyplot # list of probabilities probs = [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0] # calculate information info = [-log2(p) for p in probs] # plot probability vs information pyplot.plot(probs, info, marker='.') pyplot.title('Probability vs Information') pyplot.xlabel('Probability') pyplot.ylabel('Information') pyplot.show() |

Running the example creates the plot of probability vs information in bits.

We can see the expected relationship where low probability events are more surprising and carry more information, and the complement of high probability events carry less information.

We can also see that this relationship is not linear, it is in-fact slightly sub-linear. This makes sense given the use of the log function.

Plot of Probability vs Information

Calculate the Entropy for a Random Variable

We can also quantify how much information there is in a random variable.

For example, if we wanted to calculate the information for a random variable X with probability distribution p, this might be written as a function H(); for example:

- H(X)

In effect, calculating the information for a random variable is the same as calculating the information for the probability distribution of the events for the random variable.

Calculating the information for a random variable is called “information entropy,” “Shannon entropy,” or simply “entropy“. It is related to the idea of entropy from physics by analogy, in that both are concerned with uncertainty.

The intuition for entropy is that it is the average number of bits required to represent or transmit an event drawn from the probability distribution for the random variable.

… the Shannon entropy of a distribution is the expected amount of information in an event drawn from that distribution. It gives a lower bound on the number of bits […] needed on average to encode symbols drawn from a distribution P.

— Page 74, Deep Learning, 2016.

Entropy can be calculated for a random variable X with k in K discrete states as follows:

- H(X) = -sum(each k in K p(k) * log(p(k)))

That is the negative of the sum of the probability of each event multiplied by the log of the probability of each event.

Like information, the log() function uses base-2 and the units are bits. A natural logarithm can be used instead and the units will be nats.

The lowest entropy is calculated for a random variable that has a single event with a probability of 1.0, a certainty. The largest entropy for a random variable will be if all events are equally likely.

We can consider a roll of a fair die and calculate the entropy for the variable. Each outcome has the same probability of 1/6, therefore it is a uniform probability distribution. We therefore would expect the average information to be the same information for a single event calculated in the previous section.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

# calculate the entropy for a dice roll from math import log2 # the number of events n = 6 # probability of one event p = 1.0 /n # calculate entropy entropy = -sum([p * log2(p) for _ in range(n)]) # print the result print('entropy: %.3f bits' % entropy) |

Running the example calculates the entropy as more than 2.5 bits, which is the same as the information for a single outcome. This makes sense, as the average information is the same as the lower bound on information as all outcomes are equally likely.

|

1 |

entropy: 2.585 bits |

If we know the probability for each event, we can use the entropy() SciPy function to calculate the entropy directly.

For example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

# calculate the entropy for a dice roll from scipy.stats import entropy # discrete probabilities p = [1/6, 1/6, 1/6, 1/6, 1/6, 1/6] # calculate entropy e = entropy(p, base=2) # print the result print('entropy: %.3f bits' % e) |

Running the example reports the same result that we calculated manually.

|

1 |

entropy: 2.585 bits |

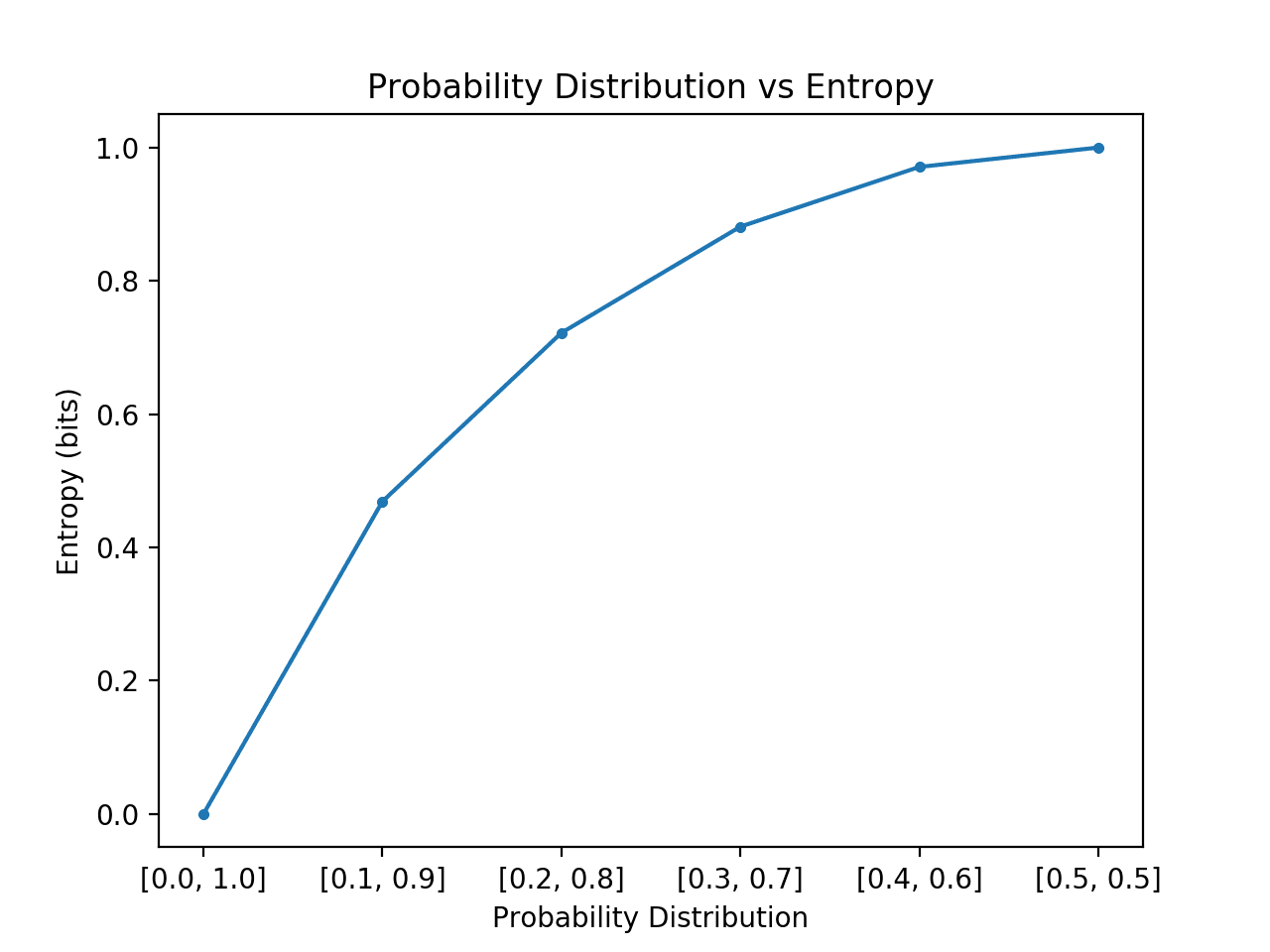

We can further develop the intuition for entropy of probability distributions.

Recall that entropy is the number of bits required to represent a randomly drawn even from the distribution, e.g. an average event. We can explore this for a simple distribution with two events, like a coin flip, but explore different probabilities for these two events and calculate the entropy for each.

In the case where one event dominates, such as a skewed probability distribution, then there is less surprise and the distribution will have a lower entropy. In the case where no event dominates another, such as equal or approximately equal probability distribution, then we would expect larger or maximum entropy.

- Skewed Probability Distribution (unsurprising): Low entropy.

- Balanced Probability Distribution (surprising): High entropy.

If we transition from skewed to equal probability of events in the distribution we would expect entropy to start low and increase, specifically from the lowest entropy of 0.0 for events with impossibility/certainty (probability of 0 and 1 respectively) to the largest entropy of 1.0 for events with equal probability.

The example below implements this, creating each probability distribution in this transition, calculating the entropy for each and plotting the result.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

# compare probability distributions vs entropy from math import log2 from matplotlib import pyplot # calculate entropy def entropy(events, ets=1e-15): return -sum([p * log2(p + ets) for p in events]) # define probabilities probs = [0.0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5] # create probability distribution dists = [[p, 1.0 - p] for p in probs] # calculate entropy for each distribution ents = [entropy(d) for d in dists] # plot probability distribution vs entropy pyplot.plot(probs, ents, marker='.') pyplot.title('Probability Distribution vs Entropy') pyplot.xticks(probs, [str(d) for d in dists]) pyplot.xlabel('Probability Distribution') pyplot.ylabel('Entropy (bits)') pyplot.show() |

Running the example creates the 6 probability distributions with [0,1] probability through to [0.5,0.5] probabilities.

As expected, we can see that as the distribution of events changes from skewed to balanced, the entropy increases from minimal to maximum values.

That is, if the average event drawn from a probability distribution is not surprising we get a lower entropy, whereas if it is surprising, we get a larger entropy.

We can see that the transition is not linear, that it is super linear. We can also see that this curve is symmetrical if we continued the transition to [0.6, 0.4] and onward to [1.0, 0.0] for the two events, forming an inverted parabola-shape.

Note we had to add a tiny value to the probability when calculating the entropy to avoid calculating the log of a zero value, which would result in an infinity on not a number.

Plot of Probability Distribution vs Entropy

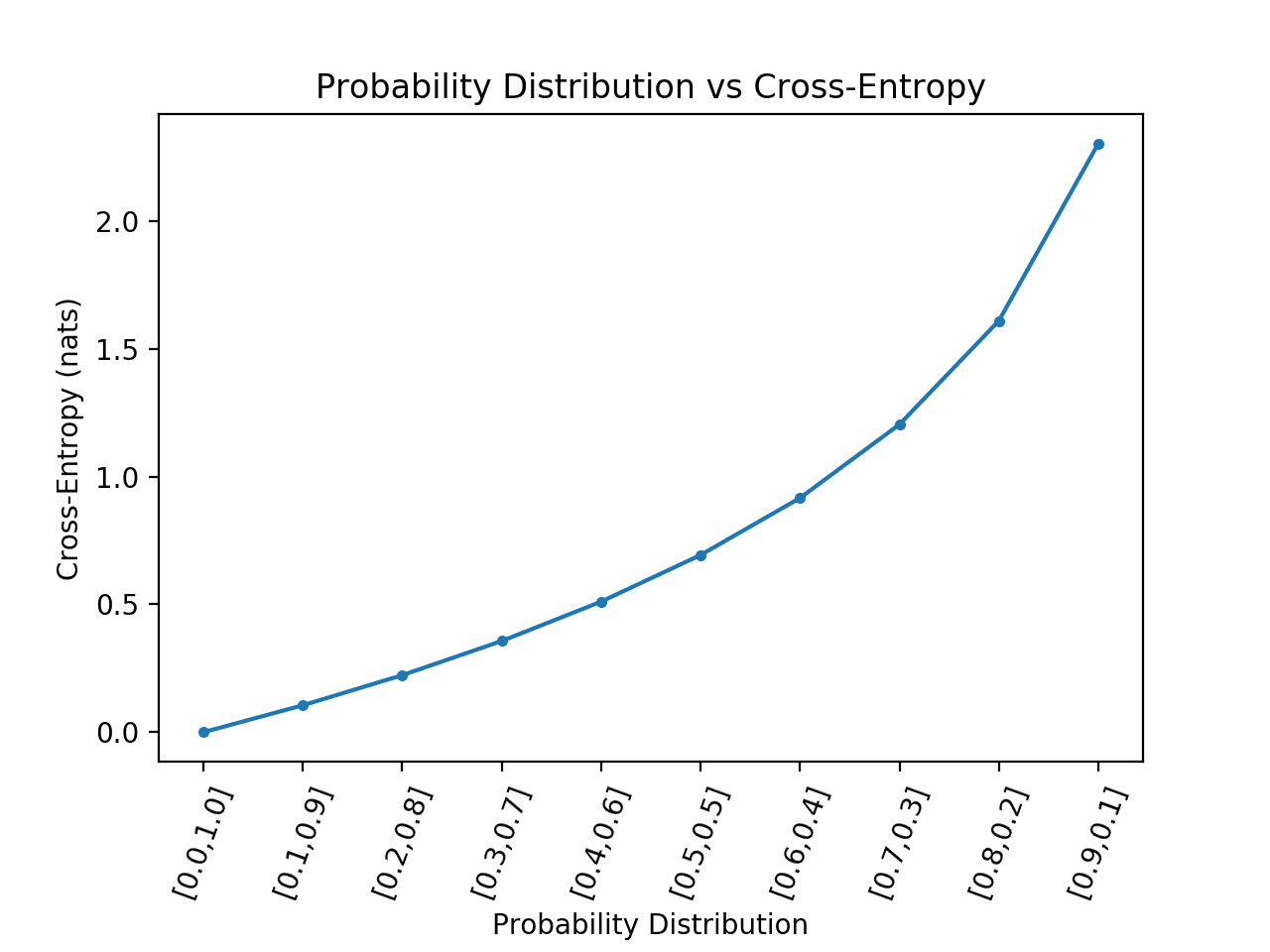

Calculating the entropy for a random variable provides the basis for other measures such as mutual information (information gain).

Entropy also provides the basis for calculating the difference between two probability distributions with cross-entropy and the KL-divergence.

Further Reading

This section provides more resources on the topic if you are looking to go deeper.

Books

Chapters

- Section 2.8: Information theory, Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective, 2012.

- Section 1.6: Information Theory, Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, 2006.

- Section 3.13 Information Theory, Deep Learning, 2016.

API

Articles

- Entropy (information theory), Wikipedia.

- Information gain in decision trees, Wikipedia.

- Information gain ratio, Wikipedia.

Summary

In this post, you discovered a gentle introduction to information entropy.

Specifically, you learned:

- Information theory is concerned with data compression and transmission and builds upon probability and supports machine learning.

- Information provides a way to quantify the amount of surprise for an event measured in bits.

- Entropy provides a measure of the average amount of information needed to represent an event drawn from a probability distribution for a random variable.

Do you have any questions?

Ask your questions in the comments below and I will do my best to answer.

Hmm, wouldn’t it better read as -sum(i=1 to K p(i) * log(p(i)))

Yes, that is better notation, thanks for the suggestion.

I’m try to walk that line between give equations but not so much that it scares people away (e.g. no latex).

“If the coin was not fair and the probability of a head was instead 10% (0.1), then the event would be more rare and would require more than 3 bits of information.”

What does it mean for an event to “require more than 3 bits of information”? Certainly, we can send information on an outcome of a binary variable using a single bit whatever the probabilities are, can’t we?

Here, we are describing the variable, not a single outcome.

If there is more or less surprise, we need more information to encode the variable – e.g. the scope of values it could have when transmitted on a communication channel.

Hi Jason,

thanks for the article, you instantly took me back 40 years to when I did this during my electronics degree.

I think I’m suffering from the same conceptual barrier that Evgenii is and, even with your reply, I’m still stuck. To state Evgenii’s question another way:

No matter what the probaility of heads or tails is there are still only two outcomes so the variable only needs to be one bit long. So in the case of 10% heads and I had 3 bits what on earth would the other two bits contain that isn’t already contained in the one bit variable?

Thanks.

The intuition is that we are communicating a variable, entropy summarises the information in the probability distribution for all events of a variable. Not any single event that is communicated one time.

How many bits of information are in x probability distribution vs y distribution? That is the focus of entropy as a measure. Perhaps drop the idea of sending bits across a communications channel, it might be confusing the issue.

Does that help?

Yes, I think so, thank-you.

What we are doing is defining a variable that holds what we are calling “information” or “entropy”; what this information conveys is unknown and irrelevant for the time being. (It certainly is NOT the outcome of any particular event).

What we can do is work out is how big this variable needs to be and that is what you have been at great pains to describe here.

Yes, great summary!

Hi Dr. Brownlee,

Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude for your outstanding articles in the Machine Learning field.

Secondly, for your argument:

“If there is more or less surprise, we need more information to encode the variable – e.g. the scope of values it could have when transmitted on a communication channel.”

Would you please elaborate on what exactly will be the scope of values that require 3 bits in the case that the probability of a head was instead 10% (0.1)?

Finally, I apologize for asking such a simple question, but I am a new student in the field and your feedback is greatly appreciated.

Best Regards,

You’re welcome.

Scope of values? It would be heads or tails.

Perhaps I don’t undertand your question?

This is a very good article, thanks 🙂

Question: Is there any way of summarising this in a way like ‘In order to transmit the’ unfairness’ of the coin, you’d need this number of bits, assuming you need 1 bit to say “fair coin”?’

I suppose I’m really trying to relate this to some form of ‘information’ that corresponds to the “3 bits of information” example being discussed, but which also seems intuitive to me. Am I on a wild goose chase? 😀

Thanks.

Yes, except the part about a fair coin. We are summarizing the transmission of events (information) or distributions (entropy) – capturing their properties in a measure rather than stating them.

The descriptions that talk about sending data across a comms channel may help. Perhaps the refs in the “further reading” section will help.

I think the weighted coin example is kind of confusing because the coin still only has two states. Whereas an eight sided die example would be better in my opinion because its clear that you need 3 bits to represent 8 states (2^3), and 1 bit to represent 2 states (2^1) ie the coin

Congrats for so many great articles! I’ve learned a lot from your explanations.

Thanks!

Can you please elaborate more on what “information” is. For example, a coin flip when given a lower probability requires more “information”. What do you mean when you use the word “information”?

I read the previous thread started by Evgenii but it did not clear it up for me.

Here’s another way to think about it:

Information is an idea of how well we can compress events from a distribution. Entropy is how well can we can compress the probability distribution of events.

When we calculate the actual number of information bits, is this unit arbitrary? Or can it be directly paralleled to number of bits a computer would need to store the information?

If the later, what would be the exact info stored on a computer between the 50% chance of success and 10% chance of success for flipping heads? I think my problem in understanding is not directly seeing what the information is.

Thank you for the posts, they always help!

Hmmm, it can be related to the compression of the variable/distribution.

It is most useful in machine learning as a relative score for comparison with other cases.

Perhaps if you gave them an overly concrete example:

Say you flipped your 10%/90% coin a million times and wanted to transfer that million-long sequence to another computer node. A very simple run length encoding would allow you to describe long runs of 90% results (let’s call that heads) in vastly fewer bits. This is exactly what you’d do if you were relaying the sequence over the phone:

“That’s one tail, followed by 5 heads, one tail, followed by 8 heads, etc.”

This immediately shows the reduced information content of each head. Now you want the description of the heads to be as compact as possible – but the data stream is now non-uniform: how do I distinguish a bit that indicates tail from a multi-bit “structure” that reflects a count (run length)? You end up creating a multi-bit structure for each tail event – a magic multi-bit structure that is not allowed within the run-length-descriptor. The less frequent tails are the greater the price you’re willing to pay to mark the tail event – because the longer that marker is, the cheaper it is to describe run length (easier to avoid the magic multi-bit code that marked the tail event).

Hope this example helps.

Very cool example, thank you for sharing!

Great Article. The plot of Shannon Entropy vs the different probability distributions is for a binary random variable.

Correct.

Stumbled across your blog! Is there any advantages/reason to calculate entropy using the base-2 logarithm VS natural logarithm?

Base-2 lets you use the units of “bits”, the most common usage.

Very well explained!

I was wondering if you could elaborate more on the usage of entropy value with real time examples. What kind of problems we would be solving ?

Thanks!

In machine learning we often use cross-entropy and information gain, which require an understanding of entropy as a foundation.

You wrote “therefore have more information those events that are common”, but you mean “therefore have more information THAN those events that are common”.

Yes, thanks. Fixed.

Hi Jason,

Can we consider the information as a special case of entropy with a uniform probability distribution (events are equally likely)?

Not really, information is about an event, entropy is about a distribution.

This sentence was a bit confusing: “More generally, this can be used to quantify the information in an event and a random variable, called entropy, and is calculated using probability.” Is the following what you meant? “More generally, this can be used to quantify the information both in an event and in a random variable (called entropy), and in both cases is calculated using probability.”

Perhaps.

Note, we measure “information” for an event. We measure “entropy” for a variable/distribution.

You can also include this video by khan academy in your resources.

https://www.khanacademy.org/computing/computer-science/informationtheory/moderninfotheory/v/information-entropy

Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for the article ^_^

Somewhere: “Recall that entropy is the number of bits required to represent a randomly drawn even from the distribution”

I think you meant “event” instead of “even”?

You’re welcome.

Thanks.

Incredibly article, really appreciate your work into this.

Not sure if this will help anyone else, but I was having trouble understanding where the 1/p came from in the log, and why 1-p or some other metric wasn’t used. What helped me gain an intuition for this was realizing 1/p is the number of bits we would need to encode a uniform distribution if every event had the probability p. So the information, -log(1/p), is how many bits that event would be “worth” were it part of a uniform distribution. I found this helpful in trying to memorize the formula. A uniform distribution would also be the maximum entropy distribution that event could possibly come from given its probability…though you can’t reference entropy without first explaining information 🙂 Anyway the mid part of this article goes into a bit more detail on it if anyone’s curious on that bit specifically https://scriptreference.com/information-theory-for-machine-learning/

Thanks for sharing Mike!

Whoops sorry, typo above… I meant to say “the information, -log(p), is how many bits that event would be ‘worth’ were it part of a uniform distribution.” Not -log(1/p).

This is because 1/p is the number of events a uniform distribution would need for each event to have a probability of p. So log(1/p) is the number of bits needed to encode all the events in that distribution in binary. log(1/p) = log(1) – log(p) = -log(p)

What are the bounds on entropy for discrete and continuous random variables?

The entropy should be between 0 and 1, but depends on the probability density function.

Hi Jason,

Great blog article and much appreciated. Still one question is still lingering in my mind. How would Shannon’s entropy (H) be applied if for example an English text prior to encryption has undergone a transformation into a random string of characters. Let’s assume a Markov process, generating for each plaintext character a random permutation and the character mapped against the permutation – m → tm. If we now apply modular arithmetic and k (Key) is a randomly selected character too, the equation becomes tm + k | mod26 = c. Shannon’s entropy requires that C (cipher) can be measured against a property, which in its own right can be measured (a meaningful English in my example). Shannon states that RMLM ≤ RKLK is required to maintain perfect secrecy when using the Vernam Cipher (today’s OTP). By transforming the plaintext the key doesn’t need to be an infinite string of symbols anymore, as Shannon suggests, because tm and k both hold a 1/26 probability. Modular arithmetic might produce a sensible ciphertext, however it most certainly won’t be the original plaintext.

Sorry, forgot to mention that the modus operandi can be applied to the hexadecimal and binary system.

Hi Jason,

Great blog article and much appreciated. Still one question is still lingering in my mind. How would Shannon’s entropy (H) be applied if for example an English text prior to encryption has undergone a transformation into a random string of characters. Let’s assume a Markov process, generating for each plaintext character a random permutation and the character mapped against the permutation – m → tm. If we now apply modular arithmetic and k (Key) is a randomly selected character too, the equation becomes tm + k | mod26 = c. Shannon’s entropy requires that C (cipher) can be measured against a property, which in its own right can be measured (a meaningful English in my example). Shannon states that RMLM ≤ RKLK is required to maintain perfect secrecy when using the Vernam Cipher (today’s OTP). By transforming the plaintext the key doesn’t need to be an infinite string of symbols anymore, as Shannon suggests, because tm and k both hold a 1/26 probability. Modular arithmetic might produce a sensible ciphertext, however it most certainly won’t be the original plaintext. The modus operandi can be applied to the hexadecimal and binary system.

Hi Wandee…Please simplify your question so that I may better assist you.

Hi,

can you recommend to me some articles on set shaping theory?

I am very interested in this new theory

Hi Aron…Thank you for the recommendation for our consideration!

In the following statement:

A foundational concept from information is the quantification of the amount of information in things like events, random variables, and distributions.

Should it instead say:

A foundational concept from information theory is the quantification of the amount of information in things like events, random variables, and distributions.

It is kind of confusing to me the way it is worded.

Hi Jason,

When using Cross Entropy Loss to train a model and find the best fit, are we trying to minimize the possibilities that the value could be (information transmitted) and hence make it less surprising?

Thank you for the thought provoking article.

Hi Jun…Thank you for the feedback! Yes…your understanding is correct.