Working on a machine learning project means we need to experiment. Having a way to configure your script easily will help you move faster. In Python, we have a way to adapt the code from a command line. In this tutorial, we are going to see how we can leverage the command line arguments to a Python script to help you work better in your machine learning project.

After finishing this tutorial, you will learn

- Why we would like to control a Python script in a command line

- How we can work in a command line efficiently

Kick-start your project with my new book Python for Machine Learning, including step-by-step tutorials and the Python source code files for all examples.

Let’s get started.

Command line arguments for your Python script. Photo by insung yoon. Some rights reserved

Overview

This tutorial is in three parts; they are:

- Running a Python script in command line

- Working on the command line

- Alternative to command line arguments

Running a Python Script in Command Line

There are many ways to run a Python script. Someone may run it as part of a Jupyter notebook. Someone may run it in an IDE. But in all platforms, it is always possible to run a Python script in command line. In Windows, you have the command prompt or PowerShell (or, even better, the Windows Terminal). In macOS or Linux, you have the Terminal or xterm. Running a Python script in command line is powerful because you can pass in additional parameters to the script.

The following script allows us to pass in values from the command line into Python:

|

1 2 3 4 |

import sys n = int(sys.argv[1]) print(n+1) |

We save these few lines into a file and run it in command line with an argument:

|

1 2 |

$ python commandline.py 15 16 |

Then, you will see it takes our argument, converts it into an integer, adds one to it, and prints. The list sys.argv contains the name of our script and all the arguments (all strings), which in the above case, is ["commandline.py", "15"].

When you run a command line with a more complicated set of arguments, it takes some effort to process the list sys.argv. Therefore, Python provided the library argparse to help. This assumes GNU-style, which can be explained using the following example:

|

1 |

rsync -a -v --exclude="*.pyc" -B 1024 --ignore-existing 192.168.0.3:/tmp/ ./ |

The optional arguments are introduced by “-” or “--“, where a single hyphen will carry a single character “short option” (such as -a, -B, and -v above), and two hyphens are for multiple characters “long options” (such as --exclude and --ignore-existing above). The optional arguments may have additional parameters, such as in -B 1024 or --exclude="*.pyc"; the 1024 and "*.pyc" are parameters to -B and --exclude, respectively. Additionally, we may also have compulsory arguments, which we just put into the command line. The part 192.168.0.3:/tmp/ and ./ above are examples. The order of compulsory arguments is important. For example, the rsync command above will copy files from 192.168.0.3:/tmp/ to ./ instead of the other way round.

The following replicates the above example in Python using argparse:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

import argparse parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Just an example", formatter_class=argparse.ArgumentDefaultsHelpFormatter) parser.add_argument("-a", "--archive", action="store_true", help="archive mode") parser.add_argument("-v", "--verbose", action="store_true", help="increase verbosity") parser.add_argument("-B", "--block-size", help="checksum blocksize") parser.add_argument("--ignore-existing", action="store_true", help="skip files that exist") parser.add_argument("--exclude", help="files to exclude") parser.add_argument("src", help="Source location") parser.add_argument("dest", help="Destination location") args = parser.parse_args() config = vars(args) print(config) |

If you run the above script, you will see:

|

1 2 3 |

$ python argparse_example.py usage: argparse_example.py [-h] [-a] [-v] [-B BLOCK_SIZE] [--ignore-existing] [--exclude EXCLUDE] src dest argparse_example.py: error: the following arguments are required: src, dest |

This means you didn’t provide the compulsory arguments for src and dest. Perhaps the best reason to use argparse is to get a help screen for free if you provided -h or --help as the argument, like the following:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

$ python argparse_example.py --help usage: argparse_example.py [-h] [-a] [-v] [-B BLOCK_SIZE] [--ignore-existing] [--exclude EXCLUDE] src dest Just an example positional arguments: src Source location dest Destination location optional arguments: -h, --help show this help message and exit -a, --archive archive mode (default: False) -v, --verbose increase verbosity (default: False) -B BLOCK_SIZE, --block-size BLOCK_SIZE checksum blocksize (default: None) --ignore-existing skip files that exist (default: False) --exclude EXCLUDE files to exclude (default: None) |

While the script did nothing real, if you provided the arguments as required, you will see this:

|

1 2 |

$ python argparse_example.py -a --ignore-existing 192.168.0.1:/tmp/ /home {'archive': True, 'verbose': False, 'block_size': None, 'ignore_existing': True, 'exclude': None, 'src': '192.168.0.1:/tmp/', 'dest': '/home'} |

The parser object created by ArgumentParser() has a parse_args() method that reads sys.argv and returns a namespace object. This is an object that carries attributes, and we can read them using args.ignore_existing, for example. But usually, it is easier to handle if it is a Python dictionary. Hence we can convert it into one using vars(args).

Usually, for all optional arguments, we provide the long option and sometimes also the short option. Then we can access the value provided from the command line using the long option as the key (with the hyphen replaced with an underscore or the single-character short option as the key if we don’t have a long version). The “positional arguments” are not optional, and their names are provided in the add_argument() function.

There are multiple types of arguments. For the optional arguments, sometimes we use them as Boolean flags, but sometimes we expect them to bring in some data. In the above, we use action="store_true" to make that option set to False by default and toggle to True if it is specified. For the other option, such as -B above, by default, it expects additional data to go following it.

We can further require an argument to be a specific type. For example, in the -B option above, we can make it expect integer data by adding type like the following:

|

1 |

parser.add_argument("-B", "--block-size", type=int, help="checksum blocksize") |

And if we provided the wrong type, argparse will help terminate our program with an informative error message:

|

1 2 3 |

python argparse_example.py -a -B hello --ignore-existing 192.168.0.1:/tmp/ /home usage: argparse_example.py [-h] [-a] [-v] [-B BLOCK_SIZE] [--ignore-existing] [--exclude EXCLUDE] src dest argparse_example.py: error: argument -B/--block-size: invalid int value: 'hello' |

Working on the Command Line

Empowering your Python script with command line arguments can bring it to a new level of reusability. First, let’s look at a simple example of fitting an ARIMA model to a GDP time series. World Bank collects historical GDP data from many countries. We can make use of the pandas_datareader package to read the data. If you haven’t installed it yet, you can use pip (or conda if you installed Anaconda) to install the package:

|

1 |

pip install pandas_datareader |

The code for the GDP data that we use is NY.GDP.MKTP.CN; we can get the data of a country in the form of a pandas DataFrame by:

|

1 2 3 |

from pandas_datareader.wb import WorldBankReader gdp = WorldBankReader("NY.GDP.MKTP.CN", "SE", start=1960, end=2020).read() |

Then we can tidy up the DataFrame a bit using the tools provided by pandas:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

import pandas as pd # Drop country name from index gdp = gdp.droplevel(level=0, axis=0) # Sort data in choronological order and set data point at year-end gdp.index = pd.to_datetime(gdp.index) gdp = gdp.sort_index().resample("y").last() # Convert pandas DataFrame into pandas Series gdp = gdp["NY.GDP.MKTP.CN"] |

Fitting an ARIMA model and using the model for predictions is not difficult. In the following, we fit it using the first 40 data points and forecast for the next 3. Then compare the forecast with the actual in terms of relative error:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

import statsmodels.api as sm model = sm.tsa.ARIMA(endog=gdp[:40], order=(1,1,1)).fit() forecast = model.forecast(steps=3) compare = pd.DataFrame({"actual":gdp, "forecast":forecast}).dropna() compare["rel error"] = (compare["forecast"] - compare["actual"])/compare["actual"] print(compare) |

Putting it all together, and after a little polishing, the following is the complete code:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

import warnings warnings.simplefilter("ignore") from pandas_datareader.wb import WorldBankReader import statsmodels.api as sm import pandas as pd series = "NY.GDP.MKTP.CN" country = "SE" # Sweden length = 40 start = 0 steps = 3 order = (1,1,1) # Read the GDP data from WorldBank database gdp = WorldBankReader(series, country, start=1960, end=2020).read() # Drop country name from index gdp = gdp.droplevel(level=0, axis=0) # Sort data in choronological order and set data point at year-end gdp.index = pd.to_datetime(gdp.index) gdp = gdp.sort_index().resample("y").last() # Convert pandas dataframe into pandas series gdp = gdp[series] # Fit arima model result = sm.tsa.ARIMA(endog=gdp[start:start+length], order=order).fit() # Forecast, and calculate the relative error forecast = result.forecast(steps=steps) df = pd.DataFrame({"Actual":gdp, "Forecast":forecast}).dropna() df["Rel Error"] = (df["Forecast"] - df["Actual"]) / df["Actual"] # Print result with pd.option_context('display.max_rows', None, 'display.max_columns', 3): print(df) |

This script prints the following output:

|

1 2 3 4 |

Actual Forecast Rel Error 2000-12-31 2408151000000 2.367152e+12 -0.017025 2001-12-31 2503731000000 2.449716e+12 -0.021574 2002-12-31 2598336000000 2.516118e+12 -0.031643 |

The above code is short, but we made it flexible enough by holding some parameters in variables. We can change the above code to use argparse so that we can change some parameters from the command line, as follows:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 |

from argparse import ArgumentParser, ArgumentDefaultsHelpFormatter import warnings warnings.simplefilter("ignore") from pandas_datareader.wb import WorldBankReader import statsmodels.api as sm import pandas as pd # Parse command line arguments parser = ArgumentParser(formatter_class=ArgumentDefaultsHelpFormatter) parser.add_argument("-c", "--country", default="SE", help="Two-letter country code") parser.add_argument("-l", "--length", default=40, type=int, help="Length of time series to fit the ARIMA model") parser.add_argument("-s", "--start", default=0, type=int, help="Starting offset to fit the ARIMA model") args = vars(parser.parse_args()) # Set up parameters series = "NY.GDP.MKTP.CN" country = args["country"] length = args["length"] start = args["start"] steps = 3 order = (1,1,1) # Read the GDP data from WorldBank database gdp = WorldBankReader(series, country, start=1960, end=2020).read() # Drop country name from index gdp = gdp.droplevel(level=0, axis=0) # Sort data in choronological order and set data point at year-end gdp.index = pd.to_datetime(gdp.index) gdp = gdp.sort_index().resample("y").last() # Convert pandas dataframe into pandas series gdp = gdp[series] # Fit arima model result = sm.tsa.ARIMA(endog=gdp[start:start+length], order=order).fit() # Forecast, and calculate the relative error forecast = result.forecast(steps=steps) df = pd.DataFrame({"Actual":gdp, "Forecast":forecast}).dropna() df["Rel Error"] = (df["Forecast"] - df["Actual"]) / df["Actual"] # Print result with pd.option_context('display.max_rows', None, 'display.max_columns', 3): print(df) |

If we run the code above in a command line, we can see it can now accept arguments:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

$ python gdp_arima.py --help usage: gdp_arima.py [-h] [-c COUNTRY] [-l LENGTH] [-s START] optional arguments: -h, --help show this help message and exit -c COUNTRY, --country COUNTRY Two-letter country code (default: SE) -l LENGTH, --length LENGTH Length of time series to fit the ARIMA model (default: 40) -s START, --start START Starting offset to fit the ARIMA model (default: 0) $ python gdp_arima.py Actual Forecast Rel Error 2000-12-31 2408151000000 2.367152e+12 -0.017025 2001-12-31 2503731000000 2.449716e+12 -0.021574 2002-12-31 2598336000000 2.516118e+12 -0.031643 $ python gdp_arima.py -c NO Actual Forecast Rel Error 2000-12-31 1507283000000 1.337229e+12 -0.112821 2001-12-31 1564306000000 1.408769e+12 -0.099429 2002-12-31 1561026000000 1.480307e+12 -0.051709 |

In the last command above, we pass in -c NO to apply the same model to the GDP data of Norway (NO) instead of Sweden (SE). Hence, without the risk of messing up the code, we reused our code for a different dataset.

The power of introducing a command line argument is that we can easily test our code with varying parameters. For example, we want to see if the ARIMA(1,1,1) model is a good model for predicting GDP, and we want to verify with a different time window of the Nordic countries:

- Denmark (DK)

- Finland (FI)

- Iceland (IS)

- Norway (NO)

- Sweden (SE)

We want to check for the window of 40 years but with different starting points (since 1960, 1965, 1970, 1975). Depending on the OS, you can build a for loop in Linux and mac using the bash shell syntax:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

for C in DK FI IS NO SE; do for S in 0 5 10 15; do python gdp_arima.py -c $C -s $S done done |

Or, as the shell syntax permits, we can put everything in one line:

|

1 |

for C in DK FI IS NO SE; do for S in 0 5 10 15; do python gdp_arima.py -c $C -s $S ; done ; done |

Or even better, give some information at each iteration of the loop, and we get our script run multiple times:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 |

$ for C in DK FI IS NO SE; do for S in 0 5 10 15; do echo $C $S; python gdp_arima.py -c $C -s $S ; done; done DK 0 Actual Forecast Rel Error 2000-12-31 1.326912e+12 1.290489e+12 -0.027449 2001-12-31 1.371526e+12 1.338878e+12 -0.023804 2002-12-31 1.410271e+12 1.386694e+12 -0.016718 DK 5 Actual Forecast Rel Error 2005-12-31 1.585984e+12 1.555961e+12 -0.018931 2006-12-31 1.682260e+12 1.605475e+12 -0.045644 2007-12-31 1.738845e+12 1.654548e+12 -0.048479 DK 10 Actual Forecast Rel Error 2010-12-31 1.810926e+12 1.762747e+12 -0.026605 2011-12-31 1.846854e+12 1.803335e+12 -0.023564 2012-12-31 1.895002e+12 1.843907e+12 -0.026963 ... SE 5 Actual Forecast Rel Error 2005-12-31 2931085000000 2.947563e+12 0.005622 2006-12-31 3121668000000 3.043831e+12 -0.024934 2007-12-31 3320278000000 3.122791e+12 -0.059479 SE 10 Actual Forecast Rel Error 2010-12-31 3573581000000 3.237310e+12 -0.094099 2011-12-31 3727905000000 3.163924e+12 -0.151286 2012-12-31 3743086000000 3.112069e+12 -0.168582 SE 15 Actual Forecast Rel Error 2015-12-31 4260470000000 4.086529e+12 -0.040827 2016-12-31 4415031000000 4.180213e+12 -0.053186 2017-12-31 4625094000000 4.273781e+12 -0.075958 |

If you’re using Windows, you can use the following syntax in command prompt:

|

1 |

for %C in (DK FI IS NO SE) do for %S in (0 5 10 15) do python gdp_arima.py -c $C -s $S |

or the following in PowerShell:

|

1 |

foreach ($C in "DK","FI","IS","NO","SE") { foreach ($S in 0,5,10,15) { python gdp_arima.py -c $C -s $S } } |

Both should produce the same result.

While we can put a similar loop inside our Python script, sometimes it is easier if we can do it at the command line. It could be more convenient when we are exploring different options. Moreover, by taking the loop outside of the Python code, we can be assured that every time we run the script, it is independent because we will not share any variables between iterations.

Alternative to command line arguments

Using command line arguments is not the only way to pass in data to your Python script. At least, there are several other ways too:

- using environment variables

- using config files

Environment variables are features from your OS to keep a small amount of data in memory. We can read environment variables in Python using the following syntax:

|

1 2 |

import os print(os.environ["MYVALUE"]) |

For example, in Linux, the above two-line script will work with the shell as follows:

|

1 2 3 |

$ export MYVALUE="hello" $ python show_env.py hello |

In Windows, the syntax inside the command prompt is similar:

|

1 2 3 4 |

C:\MLM> set MYVALUE=hello C:\MLM> python show_env.py hello |

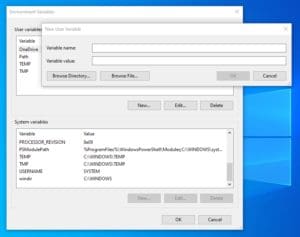

You may also add or edit environment variables in Windows using the dialog in the Control Panel:

So we may keep the parameters to the script in some environment variables and let the script adapt its behavior, like setting up command line arguments.

In case we have a lot of options to set, it is better to save the options to a file rather than overwhelming the command line. Depending on the format we chose, we can use the configparser or json module from Python to read the Windows INI format or JSON format, respectively. We may also use the third-party library PyYAML to read the YAML format.

For the above example running the ARIMA model on GDP data, we can modify the code to use a YAML config file:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 |

import warnings warnings.simplefilter("ignore") from pandas_datareader.wb import WorldBankReader import statsmodels.api as sm import pandas as pd import yaml # Load config from YAML file with open("config.yaml", "r") as fp: args = yaml.safe_load(fp) # Set up parameters series = "NY.GDP.MKTP.CN" country = args["country"] length = args["length"] start = args["start"] steps = 3 order = (1,1,1) # Read the GDP data from WorldBank database gdp = WorldBankReader(series, country, start=1960, end=2020).read() # Drop country name from index gdp = gdp.droplevel(level=0, axis=0) # Sort data in choronological order and set data point at year-end gdp.index = pd.to_datetime(gdp.index) gdp = gdp.sort_index().resample("y").last() # Convert pandas dataframe into pandas series gdp = gdp[series] # Fit arima model result = sm.tsa.ARIMA(endog=gdp[start:start+length], order=order).fit() # Forecast, and calculate the relative error forecast = result.forecast(steps=steps) df = pd.DataFrame({"Actual":gdp, "Forecast":forecast}).dropna() df["Rel Error"] = (df["Forecast"] - df["Actual"]) / df["Actual"] # Print result with pd.option_context('display.max_rows', None, 'display.max_columns', 3): print(df) |

The YAML config file is named as config.yaml, and its content is as follows:

|

1 2 3 |

country: SE length: 40 start: 0 |

Then we can run the above code and obtain the same result as before. The JSON counterpart is very similar, where we use the load() function from the json module:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 |

import json import warnings warnings.simplefilter("ignore") from pandas_datareader.wb import WorldBankReader import statsmodels.api as sm import pandas as pd # Load config from JSON file with open("config.json", "r") as fp: args = json.load(fp) # Set up parameters series = "NY.GDP.MKTP.CN" country = args["country"] length = args["length"] start = args["start"] steps = 3 order = (1,1,1) # Read the GDP data from WorldBank database gdp = WorldBankReader(series, country, start=1960, end=2020).read() # Drop country name from index gdp = gdp.droplevel(level=0, axis=0) # Sort data in choronological order and set data point at year-end gdp.index = pd.to_datetime(gdp.index) gdp = gdp.sort_index().resample("y").last() # Convert pandas dataframe into pandas series gdp = gdp[series] # Fit arima model result = sm.tsa.ARIMA(endog=gdp[start:start+length], order=order).fit() # Forecast, and calculate the relative error forecast = result.forecast(steps=steps) df = pd.DataFrame({"Actual":gdp, "Forecast":forecast}).dropna() df["Rel Error"] = (df["Forecast"] - df["Actual"]) / df["Actual"] # Print result with pd.option_context('display.max_rows', None, 'display.max_columns', 3): print(df) |

And the JSON config file, config.json, would be:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

{ "country": "SE", "length": 40, "start": 0 } |

You may learn more about the syntax of JSON and YAML for your project. But the idea here is that we can separate the data and algorithm for better reusability of our code.

Want to Get Started With Python for Machine Learning?

Take my free 7-day email crash course now (with sample code).

Click to sign-up and also get a free PDF Ebook version of the course.

Further Reading

This section provides more resources on the topic if you are looking to go deeper.

Libraries

- argparse module, https://docs.python.org/3/library/argparse.html

- Pandas Data Reader, https://pandas-datareader.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- ARIMA in statsmodels, https://www.statsmodels.org/devel/generated/statsmodels.tsa.arima.model.ARIMA.html

- configparser module, https://docs.python.org/3/library/configparser.html

- json module, https://docs.python.org/3/library/json.html

- PyYAML, https://pyyaml.org/wiki/PyYAMLDocumentation

Articles

- Working with JSON, https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn/JavaScript/Objects/JSON

- YAML on Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/YAML

Books

- Python Cookbook, third edition, by David Beazley and Brian K. Jones, https://www.amazon.com/dp/1449340377/

Summary

In this tutorial, you’ve seen how we can use the command line for more efficient control of our Python script. Specifically, you learned:

- How we can pass in parameters to your Python script using the argparse module

- How we can efficiently control the argparse-enabled Python script in a terminal under different OS

- We can also use environment variables or config files to pass in parameters to a Python script

Hi,

thank you for your article.

Another alternative is typer. I think It fits good to the Python package structure.

thank you for your article.